Homage to Dorje Paldron and Vajra Yogini!

This biography is only a drop of the nectar of A-Yu Khadro's life. As I write of her I will try to remember her presence. I am the insignificant disciple, Namkhai Norbu, and this is the story of how I met A-Yu Khadro and how I came to write her life story.

When I was fourteen in the Year of the Iron Rabbit, 1951, I was studying at Sakya College. My teacher there, Kenrab Odzer, had twice given me the complete teachings of Vajra Yogini in the Norpa and Sharpa Sakya traditions.

One day he said to me: "In the region of Tagzi, not far from your family's home, lives an accomplished woman, a great dakini, A-Yu Khadro. You should go to her and request the Vajra Yogini initiation from her.

That year he let me leave a month early for the autumn holidays with the understanding that I would be going to see A-Yu Khadro. So first I returned home and prepared to go with my mother Yeshe Chodron and my sister Sonam Pundzom.

We set off, and after a journey of three days, we arrived at A-Yu Khadro's place in Dzongsa. She lived in a little stone but near a river in a meadow under the cliff face of a mountain to the east of a small Sakya monastery.

The hut was tiny; with no windows." She had two assistants, an old man, Palden, and an old nun, Zangmo. They were also strong practitioners of yoga and meditation.

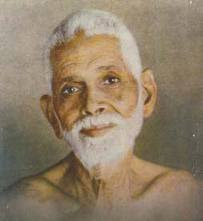

We were very happy and amazed to see this situation. When we entered Khadro's room for the first time, only one butter lamp was lit. She was 113 at that time, but she did not look particularly ancient. She had very long hair that reached her knees. It was black at the tips and white at the roots. Her hands looked like the hands of a young woman. She wore a dark-red dress and a meditation belt over her left shoulder.

During our visit we requested teachings, but she kept saying that she was no one special and had no qualifications to teach. When I asked her to give me the Vajra Yogini teachings she said: "I am just a simple old woman, how can I give teachings to you?

The more compliments we offered her, the more deferential she became toward us. I was discouraged and feared she might not give us any teachings. That night we camped near the river, and the next morning, as we were making breakfast, Ani Zangmo, the old nun, arrived with her niece bringing butter, cheese, and yogurt.

These, she said, were for the breakfast of my mother and sister, and I was to come to see Khadro. I went immediately, and as I entered I noted that many more butter lamps were lit and she touched her forehead to mine, a great courtesy. She gave me a nice breakfast of yogurt and milk and told me that she had had an auspicious dream that night of her teacher, Jamyang Khentse Wangpo.

He had advised her to give me the teachings of Khadro Sangwa Kundu, his gongter. This was not the teaching I had asked for, but was a teaching she had received from him directly which she had practiced extensively.

While we were having breakfast, she was examining the Tibetan calendar. Then she said: "Since tomorrow is the day of the dakini, we will begin then. Today go to visit the Sakya monastery, and in the meantime we will make preparations.

So we went off to visit the monastery and made some offerings there. They had statues of the Buddhas of the Three Times and a stupa five arm-lengths high made of gilded bronze and studded with many jewels. It had been made according to Khadro's instructions. Inside it was empty.

The next day around eleven we began the initiation of Khadro Sangdu. From that day on, every morning she gave teachings including the practices of the subtle nerves and the subtle breath. In the afternoon at the end of her meditation session, she gave further explanation of the Khadro Sangdu and the Chod of Machig Lapdron, the Zinba Rangdrol. This was the Chod practice she had done for many years when she was younger.

There were five of us receiving these teachings: Khenpo Tragyal, the abbot of the monastery; Yangkyi, a nun; my mother; my sister; and I. Her hut was so small that not everyone could fit in, and Yangkyi had to sit outside the doorway. The Khenpo assisted with the shrine and the mandalas.

A month later, she began the Yang-Ti, one of the most important of the Dzog Chen teachings in the most advanced Upadesha series, having to do with the practice in the dark. This teaching took five days.

Then she began teaching on the Longchen Nying Thig. This ended on the twenty-fourth.

In the seventh month on the tenth day, she gave the Vajra Yogini in the Sharpa tradition, the instruction I had requested, followed by a complete explanation. This was linked to the Kha Khyab Rangdrol teachings of Nala Perna Dundrub.

Then she gave the complete teachings of her Singhamukha Gongter which took until the tenth of the following month. At the end she gave the long life White Tara practice. Not only did we receive formal teaching, but in addition, she made time for informal conversations and personal advice.

I was not with her a long time, a little more than two months. During that time she [gave] eight kinds of teachings and was really so kind and gentle. We were very content with the generous gift of these precious teachings.

The Khenpo, one of her principal disciples, told us that he had, from time to time, received teachings from her, but the kind and extent of the teachings she had given us were rare indeed. She normally did not give much teaching and had never given so much in such a short time. He was afraid this meant that she might pass away very soon.

Then Palden, the old man, said that several months before we came she had had a dream indicating that she should give certain teachings soon. Before we arrived they had begun the preparations. So there was definitely a motive for giving these teachings.

Sometimes, at my request, after the afternoon teachings, she would tell me about her life. I had the peculiar habit of writing everything down, unusual for Tibetans, so I wrote down everything she told me. From these notes I constructed this biography. What follows is what she herself told me.

I would ask her a question, for example about her birth and childhood, and she replied: "I was born in the Fourteenth Rabjung in the Year of the Earth Boar, 1839, during the winter, on the day of the dakini.

The Togden who lived on the nearby mountain, Togden Rangrig, was at our house when I was born. He named me Dechen Khadro, which means "great bliss dakini. Some people also reported some auspicious signs on the day of my birth.

I was born in Tagzi in the village of Dzong Trang in the family of Ah-Tu Tahang. In ancient times this had been a very rich family, but when I was born we were neither rich nor miserably poor.

My father's name was Tamdrin Gon, but he was called Arta. My mother's name was Tsokyi, but she was called Atso, and they had three sons and four daughters.

All the sons became traders and all the daughters did nomad's work, looking after animals. Since I was the youngest and the weakest, I was sent to look after the small animals and given the worst clothes. This is the story of my birth and childhood.

Then I asked her how she had met a teacher and begun to practice meditation. She said: "My aunt Dronkyi was a strong practitioner and lived near the cave of Togden Rangrig in another cave. From childhood she had been interested in meditation, and I, too, was strongly drawn to the teachings. I went to this place, Dragka Yang Dzong, by my own choice when I was seven. I stayed there until I was eighteen, in 1856.

I assisted my aunt, bringing her water and fire wood. I also assisted a disciple of the Togden, Kunzang Longyang, and he taught me and his nephew Rinchen Namgyal to read and write Tibetan. I began to become quite good at reading because the disciples of the Togden decided to read the Kangyur twice to extend the Togden's life and I participated in this.

When I was thirteen, I received initiation and teaching on the Longsal Dorje Nyingpo. I also received the explanation and did my best to participate fully; although I had no understanding of the teaching really, I had much faith. A man called Apho Tsenga came to receive this teaching. He was from the rich family of Gara Tsong in the region of Nya Shi, who were friends of my aunt.

My parents also attended the teachings, but their minds were not on the teachings, but rather on my future. By the end of the teaching I had been betrothed against my will to Apho Tsenga' s son. I had no idea, really, what it meant, but I understood an interruption to my practice was being planned.

My aunt did her best to intervene, but my parents were interested in the wealth of the Cara Tsong family. They only consented to the wedding be delayed a few years.

When I was fourteen, I went with my aunt and Togden Rangrig to see Jamyang Khentse Wongpo, Jamyang Kongtrul, and Cho Gyur Lingpa, three great lamas, gathered together to consecrate a certain place. It was a seven-day journey to Dzong Tsho, and there we also met a lot of other teachers and great masters and received much instruction.

My desire to participate more fully in the teachings increased at this time, particularly when we stopped to see Situ Rinpoche at Pema Nyingkye on our way back. From him we received teaching on White Tara. After this we returned to the Togden' s retreat place, and he and my aunt went straight into retreat. I began doing the preliminary practices of the Longchen NyingThig in my spare time. I was instructed by Kunzang Longyang.

When I was sixteen, in the Year of the Wood Tiger 1854, my aunt and I went to see Jamyang Khentse Wongpo. When we arrived, we heard that he was in very strict retreat, but we sent him a message saying we had come from Togden Rangrig.Since we had come from so far away with great self-sacrifice, he agreed to see us.

When we met him, he told us that the preceding night he had had a dream which indicated he should teach us. He had decided to initiate us into the Pema Nying Thig, his White Tara gongter. During the initiation he gave me the name Tsewang Paldron.

For more than a month, every time he finished a session he gave us teachings. I began to get some idea of the meaning of the teachings at this time and when we returned to Togden' s place, I entered a White Tara retreat.

When I was nineteen, in the Year of the Fire Serpent, 1857, my parents and my brothers and sisters all decided it was high time I got married. They began to make great preparations for my marriage, and my aunt was very worried. She felt responsible for introducing the Gara Tsong family to my parents.

It was against her advice that they proceeded with my marriage. She pleaded that I should be left to do what I wanted to do and that my practice should not be interrupted. But my parents insisted on marriage - not for my happiness, rather for their gain.

The wedding took place towards the middle of the summer. It was a very happy occasion; even Togden Rangrig came to the wedding and showered blessings on us. It seemed as if we would be happy.

I stayed for three years with the Gara Tsong family, and my husband, Apho Wangdo, was very kind and generous. Then I fell ill and slowly weakened for two years. The sickness could not be diagnosed.

Sometimes it seemed like a prana disease, 19 at other times I had convulsions like epilepsy; sometimes it seemed like a circulation problem. In short none of the doctors could help or even distinguish what the problem was. Whatever ritual or medicine was advised had little effect.

I became worse and worse and was near to death when they finally asked Togden Rangrig to come to see me. He gave me a long-life initiation and performed a ceremony to call the spirit back into the body and many other rituals. Both he and my aunt insisted that the real cause was that I was being forced to lead a worldly life and stay in that household against my will. They told my husband and his family that I must be allowed to leave and follow my heart. They told them about the signs at my birth and my encounters with Jamyang Khentse Wongpo. Finally, they convinced them that marriage was a blockage of innate propensities to the extent that it was endangering my life force.

My husband was a very kind man and agreed that if married life was endangering my life, it must be stopped. I told him that if he genuinely understood and loved me, he would want to follow the Togden's advice and let me be free to go and do as I pleased. I also told him that I would welcome his assistance in my retreat and hoped we could have a relationship of spiritual brothers and sisters, and if he agreed, perhaps I would get better.

He promised to do this, and who knows whether it was because of giving his word or the rituals of the Togden but after a while I began to get better. As soon as I was strong enough, he accompanied me to the caves of the Togden and my aunt. It took me a year to recuperate. I was helped very much because he made offerings to a nun there with the understanding that she would serve me and help me with the necessities. He and his sister also brought me food and supplies, acting as my patrons.

That year, I received the termas of Guru Chowang. During this time I had a dream indicating that the passing away of Togden Rangrig was imminent. When I told him this dream he said: 'I have already given you all the teachings I received from my gurus Motrul Choying Dorje, Migyur Namkhai Dorje and Rigdzin Pema Dupa Tsel. I asked him to give me a practice to extend his life; I did this and he lived another three years.

During this time I received teachings from him of Guru Nyang Ralpa on the Dzog Chen of Nyima Dragpa and many other teachings. Then, with the experienced guidance of my aunt, I began to do a lot of practice.

When I was twenty-seven in the Year of the Iron Bull, 1865, and Togden Rangrig was seventy-seven, he fell ill, and one morning we found he had left his body. He remained in the meditation posture for more than seven days. We made many offerings, and many people came to see him.

After the seventh day, we found that his body had shrunk to the size of an eight-year-old child. He was still in position and everyone continued to pray."As we were making the funeral pyre and preparing the body to be burned, everyone heard a loud noise like a thunderclap. A strange half-snow half-rain fell. During the cremation, we sat around the fire chanting and doing the One 'A' Guru Yoga practice from the Yang-ti teachings. At the end there is a long period of unification with the state.

When this was over we discovered that my aunt had left her body. She was sixty-two at the time, and when everyone else got up she didn't, she was dead. She was in perfect position and remained in the seated posture for more than three days. We covered her with a tent and remained in a circle around that tent day and night, practicing.

Everyone was saying what an important yogini she was. Previously no one had said this. After three days, she was cremated on the same spot where the Togden had been cremated. Although everyone spoke well of my aunt, I was terribly sad. I felt so lonely after the death of both the Togden and my aunt even though it was a good lesson in transience and the suffering of transmigration.

Many people continued to hear sounds from the funeral pyre for many nights. I decided to do a three-year retreat in my aunt's cave. I was assisted by the Togden's disciples and thus had good results from the retreat.

When I was thirty, in the Year of the Earth Dragon, Kunzang Longyang, the nun that had been serving me, and I began to travel around practicing Chod. We decided to visit Nala Perna Dundrub, also called Chang Chub Lingpa, as had been indicated by Togden Rangrig. We visited many sacred places and various monasteries on the way, so the journey took more than a month and a half. When we arrived at Adzom Gar, we met Adzom Drukpa and his uncle Namkhai Dorje.

They told us that Nala Perna Dundrub was expected shortly. Since Namkhai Dorje was giving teachings on the Longde to Adzom Drukpa and a group of about thirty of his disciples, we joined the group and received these teachings. The young Adzom Drukpa reviewed the teachings we had missed before we arrived.

Toward the beginning of the sixth month, Nala Perna Dundrub arrived. When he gave the great initiation on the Tshog Chen Dupa, including Adzom Drukpa and Namkhai Dorje, we were about one thousand people.

He also gave teachings on Tara, Gonpa Rangdrol, the root text about the practice at the time of death, and finally the Khal Khyab Rangdrol, his own Gongter. Namkhai Dorje and Adzom Drukpa gave more detailed explanations of the essential teachings of DzogChen. Thus we received not only initiations, but practical explanations of how to do the practices.

Kunzang Longyang and the nun I had come with decided to return to Togden Rangrig's place and I decided to go to visit Dzog Chen monastery and Sechen monastery with some of Adzom Drukpa's disciples. One of the people I traveled with, Lhawang Gonpo, was a very experienced Chodpa, and I learned a lot from him.

When we arrived at DzogChen monastery, winter was approaching, and it was becoming colder every day. Lhawang Gonpo taught me the inner heat practice and the practice of living on air and mineral substances, and so, thanks to his skillful instructions, I was able to live there quite comfortably in the bitter cold winter.

We visited many lamas and other teachers at Dzog Chen monastery, and it was during this winter that I met my friend who was the same age as me, a nun called Tema Yangkyi. We became dose friends and traveled together for years.

When we were thirty-one, in 1869, Lhawang Gonpo, Tema Yangkyi, and I went to try to see Dzongsar Khentse Rinpoche with a khenpo of Dzog Chen monastery called Jigme and ten of his disciples. Along the way, we visited Dege Gonchen monastery, where they had the woodblocks for the Kangyur. We also visited other interesting places and slowly made our way to see Dzongsar.

When we got there, to the place called Tashi Lhatse, we discovered that Dzongsar was in Marsho in strict retreat. So Khenpo Jigme and his disciples went off to visit Kam Payal monastery. Lhawang Gonpo, Perna Yangkyi, and I decided to go to Marsho with the intention of either seeing Dzongsar Jamyang Khentse Rinpoche or remaining in retreat near his retreat place.

We made our way there begging, and when we arrived, found he was, in fact, in strict seclusion. We could not even send him a message, so we camped among some rocks below his retreat and began to do some intensive practice ourselves.

We were there for more than a month before a monk called Sonam Wongpo came by one day to see what we were doing there. We told him where we were from and what we had been doing and that we had hoped to see Khentse Rinpoche. This became an indirect message to Dzongsar Khentse Rinpoche.

One day, a while later, the same monk came back and told us that Khentse Rinpoche would see us following his meditation period that morning. We were elated, and when we entered his room, he called me by the name Tsewang Paldron that he had given me.

He had decided to give us teachings on the Khadro Sangdu between his meditation sessions, since he knew us to be serious practitioners of meditation, but we were not to utter a word of this to anyone or it would become an obstacle for us. Since in two days' time it would be the anniversary of Jomo Memo's entrance into "the body of light," he thought that on that day we should begin the teachings, so in the meantime, we went out begging to get enough supplies for ourselves and to offer feasts when it was appropriate.

We took much teaching from him and still had plenty of time to practice. Then we returned with him to Dzongsar, and along with hundreds of other monks, nuns, and yogis, we received the Nying Thig Yabzhi, which took more than three months. It seemed to me that during that period, I really understood something about DzogChen.

He also gave us teachings from all the schools, the Kama Terma, Sarma, and Nyingma schools, for more than four months. We attended these teachings and met teachers from all over Tibet and received teachings from them as well. Afterwards we felt it was time to do some practice.

When we were thirty-two, in 1870, we went to see Nala Perna Dundrub in Nyarong; we went with some disciples of Dzongsar Khentse who were from Nyarong. Traveling slowly we eventually arrived in the region of Narlong in a town called Karko, where Nala Perna Dundrub was giving the Longsal Dorje Nyingpo initiation. We received the rest of this teaching and the Yang-ti Nagpo. We were there more than three months.

After this we went with Nala Perna Dundrub to Nying Lung to the area of Tsela Wongdo, where he gave the Kha Khyab Rangdrol. When this teaching had come to an end, he called for Perna Yangkyi and me. He had named my friend Osel Palkyi, 'Glorious Clear Light' and me, Dorje Paldron, 'Glorious Indestructible Vajra' during this teaching, and addressing us with these names, he said: 'Go to practice in cemeteries and sacred places. Follow the method of Machig Lapdron and overcome hope and fear. If you do this you will attain stable realization. During your travel you will encounter two yogis who will be important for you. One will be met in the country of Tsawa and the other in Loka, Southern Tibet. If you meet them, it will definitely help your development. So go now and practice as I have instructed.'

He presented us each with a Chod drum, and after further advice and encouragement, we saw no reason to delay and set off like two beggar girls. Our only possessions were our drum and a stick.'We visited Kathog and Peyul monasteries and many sacred places, encountering many teachers. Eventually we arrived at the caves of Togden Rangrig, where I had lived as a girl. I had been gone three years, and it certainly gave us a desolate feeling.

We found only an old disciple, Togden Pagpa, an old nun, and Chang Chub, a younger nun that I'd known, and Kunzang Longyang. It made me very sad to be there. When we said we were going to Central Tibet, Kunzang Longyang said that he would like to come with us. So we stayed for two weeks. As he made his preparations, we practiced Guru Yoga, made feast offerings, did practice of the guardians, and so on with the old disciples of Togden.

We were thirty-three in 1871, and it was the third month on the tenth day of the Year of the Iron Sheep that we made a fire puja and set off for Central Tibet. We traveled with about twenty other people who were on their way to Central Tibet. We followed them for about a month until we arrived in the region of Tsawa.

When we reached Tsawa, we slowed down and began our pilgrimage, begging here and there. One day we arrived at a big plateau called Curchen Thang. We approached a large encampment of nomads to ask them for food. We stood at the edge of the camp and began to sing Chod.

A young robust woman came toward us and as she approached we could see she was crying. She rushed to us and said: 'Thank goodness you Chodpas have come! Please help me! The day before yesterday my husband was killed for revenge in a feud. He is still lying in the tent. It is not easy to find a Chodpa in this part of the country. Please help me take care of his body.

We were rather at a loss as none of us were really experts at funerals, but she was so desperate, we agreed to do our best. We asked her: 'Is there a good cemetery around here?'. She replied: 'Toward the south, about half a day's journey from here, there is an important cemetery. If that is too far, there are other, smaller ones closer.

We decided to go to the larger one, and the next day in the morning we set off with someone carrying the corpse. As we were approaching the cemetery, we heard the sound of a drum and bell. As we got closer, we heard the sound of a beautiful voice singing the Chod. As we entered, we saw a Chodpa at the center of the cemetery.

He was quite young with a dark complexion and a big turban of matted hair, wrapped around his head. He wore a dark-red robe and was singing the feast offering of the Chod. At that moment we were reminded of Nala Perna Dundrub's prophecy that we would meet a Chodpa who would help us in Tsawa.

When we arrived at the center of the cemetery with the corpse, he stopped singing. He asked: 'Who among you is Dorje Paldron? Where have you come from? What are you doing here?' I said: 'I am called Dorje Paldron. These are my friends, Osel Wongmo (previously called Pema Yangkyi) and Kunzang Longyang. We are disciples of Nala Pema Dundrub. We are going to Central Tibet practicing the Chod in various charnel grounds on the way. We happened upon this situation and the family requested that we take care of this murdered man, so we brought him here. Who are you?'.

He replied: '1 am a disciple of Khentse Yeshe Dorje, my name is Semnyi Dorje and I was born in Kungpo. I have no fixed abode. I have been practicing here for the last few days. Several days ago when I was between sleeping and waking, I received a communication that someone called Dorje Paldron was coming. Since then I have been waiting for you, and that's why I asked which one of you is Dorje Paldron. Welcome! But a murdered corpse is not a simple matter to offer to the vultures. If you are not sure how to do it, maybe we can do it together.

We were very happy and set to work immediately on the funeral. We practiced together for seven days, and the relatives of the dead man brought us food. Togden Semnyi gave us teachings on the Zinba Rangdrol Chod, and we became a party of four. We traveled at a relaxed pace begging on the way, stopping a few days here and there to practice at special cemeteries, sometimes stopping at length.

After a few months we arrived at Ozayul, near Assam, and went to Tsari, where there was a temple called Phagmo Lhakang in the area of Chicha. We traveled up and down in that area for a year and three months. We went to many important places to practice.

Then in the sixth month of the Monkey Year, 1872, Kunzang Longyang fell ill with a terrible fever. We called doctors and did many practices, but he did not get better and towards the end of the sixth month he left his body. He was fifty-six years old.

When we performed the funeral, there were many interesting signs, like a huge rainbow so large everyone for miles around saw it, and it remained for the whole funeral. The local people were convinced a Mahasiddha had died. They honored us very much and we stayed there more than three months doing practice for Kunzang Longyang.

After this we went to jar and then on to Lodrag and visited all the sacred places there. This is the country of Marpa the Translator, where Milarepa's trials took place. On the tenth day of the tenth month, we reached Pema Ling and did a feast offering. There is a huge lake at Pema Ling, and many saints and yogis have lived around it, including Guru Chowang.

That night we decided each to practice separately in different places around the lake. Pema Yangkyi went to a place called Rona, and when she arrived she saw a yogi practicing there. He said to her: 'Three months ago I was practicing in Ralung, the original seat of the Drukpa Kagyu lineage, and I had a vision of Dorje Yudronma. She gave me a little roll of paper about as long as my finger. I quickly unrolled it and it said 'In the tenth month on the tenth day go in practice at a place called Rona.

She realized this was the yogi Nala Pema Dundrub had predicted we would meet in Southern Tibet. After the evening practice, he came back to the main temple with her and thus we became four again. This yogis name was Gargyi Wanchug, but he was called Trulzhi Carwang Rinpoche, and he was a disciple of the famous woman Mindroling Jetsun Rinpoche who taught on the DzogChen Terma of Mindroling.

He had a large following around Pema Ling. His disciples requested Chod teachings, and so we also became his disciples and stayed to hear his teachings. We stayed there until the tenth of the third month practicing intensively. We did 100,000 feast offerings from the Chod practice, and there were many patrons to help us.

Although we had previously planned to go to Samye, we decided to go with Trulzhi Garwang to Western Tibet to see Gang Rinpoche. So we traveled at a leisurely pace toward Yardro, where there is a huge lake, and then on to Ralung. We stayed there more than a month while he gave some of his disciples teaching in the Ati Zadon in the tradition of Mindroling. We were happy to receive such a precise explanation and were treated very well.

Then we set out for Gyaltse, Shigatse, Sralu, and Sakya, and all the principal places in Tsang. We did purification and Chod practice in all these places and then in the summer arrived in Tingri where Phadampa Sangye had lived. After staying there for a while, we went to a place called Nyalam and then with great difficulty, we went into Nepal.

We stayed at Maratika doing White Tara practice for long life and Pema Nying Thig of Jamyang Khentse Wongpo. Togden Trulzhi asked Pema Yangkyi and me to give him the transmission of this, and since we had it we did our best to give it to him.

Then we went on to Kathmandu and toured the Great Stupa and other pilgrimage places in the Kathmandu valley for a month or so, practicing and making offerings. Then we did another month of Chod, which fascinated the people, and we began to receive many invitations and became a bit better off.

Trulzhi Garwang Rinpoche said that this fame was an obstacle to the practice, a demonic interruption. So we left for Yanglesho and visited a Vajra Yogini temple in nearby Parping. Next to this is the temple of Dakshinkali. down by the river. Here there is an important Hindu temple, and we went to the nearby cemetery, which was an excellent one for Chod.

But after a few days and nights we were disturbed by people, not spirits. So we went back to Yanglesho and stayed there near the cave and Todgen Semnyi gave Togden Trulzhi the transmission of a particular Vajra Kilaya practice he had. We practiced it for several days and then decided to leave Nepal. We headed for Dolpo, and through Purang we arrived at Kyung Lung, where there was a cave in which Togden Trulzhi had stayed before.

We stayed there and in the first month of the first year, we received the Kadro Nying Thig from Trulzhi Rinpoche. We received a very elaborate complete version and stayed there for more than three months. It was a beautiful retreat. At Trulzhi Rinpoche's request we did our best to give the transmission of the Khadro Sangdu we had received from Jamyang Khentse Wongpo.

At the beginning of the fifth month, places around and on the mountain for over three years, always practicing everywhere. Then Trulzhi Pinpoche and Pema Yangkyi decided to stay on there, and I decided to return to Central Tibet with Togden Semnyi. In the second month of the Year of the Fire Bull, we said good-bye and we left, making our way slowly to Maryul doing Chod at all the interesting places along the way.

We stopped at Jomo Nagpa, the former residence of Taranatha, and many other places beneficial for practice. In the fourth month, we stopped at Tanag and Ngang Cho, where there lived a great DzogChen master, Gyurme Perna Tenzin who was giving teaching on DzogChen Semde his speciality.

We stayed there more than nine months and received complete teachings in the eighteen series of Dzog Chen, including initiations and explanations. Then we met some pilgrims who had come from Kham, and they told us that, several years before, Nala Perna Dundrub had taken the Body of Light, and this had made him very famous. We were both joyful and sad on receiving this news.

When I was forty, in 1878, Togden Semnyi and I left for Central Tibet. We went through Ushang, where there is a famous shrine of the Blue Vajra Sadhu, protector of DzogChen. We traveled all over that area on pilgrimage practicing a bit everywhere.

During the fourth month, we sighted Lhasa. We visited all the holy places of Lhasa and met many famous people. Then we visited the nearby monasteries of Sera, Drepung, and Trayepa, Gaden, Katsai, Zvalakang. Then we went on to Yangri, Drigung, and Tigrom. We always did a bit of practice everywhere we went.

Then we returned to Lhasa, where I became seriously ill. For nearly two months I was severely sick with a very high fever which led to paralysis. The doctors succeeded in lowering the fever but the paralysis continued to worsen. Togden Semnyi did special Chod practices to clear up the paralysis, and finally after two months I started to get better. It took another month to start moving and recuperate.

In the eleventh month, we decided to go to Samye for the New Year celebration. We did many days of feast offering of the Ringdzin Drupa. In the first month, we left for Zurang and visited Gamalung, a Padma Sambhava spot, and Wongyul, and then we sighted the Red we were guided to Mount Kailash by Trulzhi Rinpoche.

We stayed in many caves and sacred House at the Copper Mountain, and stayed in the cemetery there. This was the former residence of Machig Lapdron. We stayed there for three months practicing the Chod. After this, we went to Tsethang and Tradru, and from there we went to Yarlung Shedra, another place that Padma Sambhava empowered.

Then we went on to Tsering Jung, where Jigme Lingpa had had his residence. We went on up and down for more than eight months. When I was forty-two, in 1880, in the second month, we arrived at Mindroling. We visited Zurkar and Drayang Dzong, and the Nyingma monastery Dorje Deal as well as Ushang Do and Nyethang and Talung, and also Tsurpu, where the Karmapas resided. We met many teachers and received many teachings during our travels.

In the fourth month of 1880, we arrived at Payul and Nalandara and LangThang, one of the residences of the Khadampa school. Then we arrived at Na Chu Ka and headed towards Eastem Tibet.

In the seventh month, we arrived at Kungpo, where Togden Semnyi had been in retreat in the region of Kari at Deyang. In those caves there was another yogi, a monk and some nuns. When they saw Togden Semnyi, they were very happy. I stayed there for more than a year practicing and deepened my understanding of the Zinba Rangdrol Chod. Togden Semnyi gave me teachings in the Yang Sang Tug Thig, the most secret DzogChen gongter.

In the Year of the Iron Serpent, 1881, I decided to travel on to my home country. I met some traders on their way to China who were to pass through my country, so I decided to travel with them. When we got to the place I had lived when I was married, I said my farewells to the traders and did some invocations to protect them on their ventures and set out in the direction of Togden Rangrig's retreat center.

When I approached the spot, I made some inquiries as to what had happened there, but most people had never heard of the place. A few remembered that a yogi had lived there years before, but, they said, he had died and the few who remained had either left or died. I decided to go there anyway.

The place was in ruins. The wooden doors and window sills had been pulled out by the local people to be used elsewhere and I could not even recognize the caves of my aunt and Togden Rangrig. I stayed the night there. I felt very sad and did some practice. The next day I went down the mountain a bit to the cemetery to stay and do Chod.

The following morning, I had a vision when I was between sleeping and waking of an egg-shaped rock in Dzongtsa, which I could enter through a cave. When I got inside, there was a very intense darkness which suddenly was illuminated by multi-colored light streaming out of it. This illuminated the cave and pierced the walls so that I could see through to the outside. Then I awoke, and seeing this as a good indication and (since I'd heard there was in fact such a place), I left for Dzongtsa.

When I arrived I found the place. It was near Dzongtsa, but was on the opposite side of the river from where I was. I decided to camp on a nearby hill and wait for some help or for the river to go down so I could cross. But it was autumn and the river was very high. I practiced day and night, and during the third night, after midnight, something inexplicable happened to me.

I had fallen asleep and a long bridge appeared. It was white and reached the other shore near the rock I had dreamed of. I thought, 'Good, finally I can cross the river: So I crossed, and when I awoke I was actually on the other side of the river. I had arrived but I did not know how.

I put my tent on the spot where I had landed and stayed there practicing Chod for more than a month. I was assisted by a nomad, Palden, who lived nearby. He supplied me with cheese and yogurt, etc., and from time to time people came by. But even if they had known me before, they did not recognize me.

In late autumn, an epidemic broke out among the nomad's animals. I was asked to intervene, which I did with the Chod and fire practice. The epidemic stopped and everyone began to say I was a great practitioner. As they began to honor me, I was worried remembering that Trulzhi Rinpoche had said this was a demonic interruption. So I entered a stricter retreat.

After a month or so, my former husband arrived with his second wife and daughter. He had heard of my arrival and brought me many supplies. We had a very good rapport; I gave him teachings, and he asked if he might build me a house.

I told him I would like it to be right on the same spot and explained to him how I wanted it built. They invited me to their house for the winter. As it was very cold that year and his parents had died, I went to their house and meditated for the benefit of the deceased for about three months.

My father and siblings with many nieces and nephews came to see me and I helped them as much as possible by teaching them. When I was forty-four, in the Year of the Water Horse, 1882, in the third month, my husband and others began my hut.

I decided to go to see my master Khentse Rinpoche. I arrived on the tenth day of the fourth month and received many teachings and he clarified all my doubts. Then I left for Adzom Gar and met Adzom Drukpa and Drodul Pawn Dorje. I received his gongter, and all the NyingThig transmissions.

Adzom Drukpa asked me to stay and do a retreat at Puntsom Gatsal near Adzom Gar where he had been in retreat, which I did. In the second month of the Year of the Wood Monkey, 1884, Adzom Drukpa and his disciples went to see Jamyang Khentse Wongpo at Dzongsar and I went with them. Because Adzom Drukpa had requested it, he gave us the Gongpa Zangthal.

Both Adzom Drukpa and Khentse Wongpo told me to return to Tagzi, where I had landed after crossing the river in my dream. So I left immediately, stopping only to see Kongtrul Rinpoche and receive teachings on the Six Yogas of Naropa and to learn from the others who were there taking teachings. On the eighth, I returned to Tagzi, and my former husband and other faithful people had built me a hut precisely according to my instructions.

At this point I lacked nothing and decided to go into retreat. My eldest sister's daughter had become a nun a few years before and she wished to act as my assistant. As she was also very committed to practice, I accepted her offer.

So in the Year of the Wood Bird, 1885, in the first month on the day of the dakini I began a seven-year retreat. From the beginning I spent most of my time doing the practice in the dark. At first this was sometimes difficult so I alternated the dark and light, but the majority of the time was spent in complete darkness.

When I was fifty-three, in the Year of the Iron Rabbit, 1891, in the fifth month on the day of Padma Sambhava, when I was doing practice in the dark, I had a vision. I saw a very clear sphere; inside it were many dakinis carrying another sphere with the form of Jamyang Khentse Wongpo inside. I was sure this meant that he had been invited by the dakinis to leave this world of suffering.

Although I still had seven months before the end of the seven years I had promised myself to complete, I decided it was more important to see him before he left his body. So I left my hut and a few days later went directly to him in Dzongsar, accompanied by my niece.

We reached him without obstacles, and he was very kind and taught me a lot; most importantly, he clarified my practice by answering all of my questions. When I told him the vision I had had of him being carried away, I requested that he remain longer.

He said that all that is born must die and that his death could not be delayed. He told me it would be best for me to return to my retreat but and continue my practice in the dark. With great sadness I left him and returned to my hut.

When I was fifty-four, in the Year of the Water Serpent, 1892, I received the news of his death. At that moment I decided to stay in retreat for the rest of my life. So I alternated the practice in the dark with the practice in the light.

When I was fifty-six, in the Year of the Wood Horse, 1894, both my mother and the wife of the nomad Palden who had been serving me died. I did the practice of the Korwa Dongtru for them for several months. Then Palden came to serve me here.

When I was sixty in the Year of the Earth Dog, 1897, my husband Apho Wangdo died, so I did purification for him and his family for an extended period of time.

At the end of autumn in the Year of the Iron Mouse, 1900, my old friend Pema Yangkyi appeared unexpectedly. She brought the news that in the third month of the previous year, 1899, Trulzhi Rinpoche, at the age of eighty-three, had passed away taking the body of light and leaving no corpse. She told me the whole story of how this had happened in his cave on Mount Kailash.

She stayed in my tiny hut with me for a year and we did retreat together. This was a big boon for me; it really helped the development of my practices. After a year she left for Kawa Karpo, a mountain in Southern Tibet which had been indicated by Trulzhi Rinpoche as the place she should go to. I later heard that she lived there for many years and had many students.

Then in the Year of the Iron Boar, 1911, she took the body of light at the age of seventy-four. After her departure her students came to me for teachings and told me stories from her life and about her death.

Then in the Year of the Wood Tiger at the end of summer, some disciples of Togden Semnyi came and told me he had sent them to me specifically. They told me that he had not remained in Chumbo but had traveled toward Amdo on pilgrimage, practicing everywhere.

At the end of his life they went towards China to Ribotse Na. He stayed there teaching for three years and had many disciples, both Chinese and Tibetan. At the age of eighty-five he passed away and there were many auspicious signs and many ringsel in his ashes.

Realizing that all of my friends had left the world made me very conscious of impermanence, and I was inspired to practice as much as possible with the time I had left. I taught Togden Semnyi's disciples for several months and then sent them off to various places to practice meditation.

That is the end of what A-Yu Khadro told me herself. The rest is the story of the passing away as I heard it. She told me these stories, gave me much wise counsel, and then I returned to my master at the Sakya College.

That year I finished college. In the Year of the Water Dragon, 1952, in the eighth month, I went to Sengchen Namdrag, where my uncle had been in retreat. I did a Simhamukha retreat and various other practices there.

I had a dream while I was there of a brilliant crystal stupa which appeared to be being pushed toward the West. Slowly it disappeared in space and at that moment I heard a voice saying: "This is the tomb of Dorje Paldron.

The voice woke me up and I felt really very empty inside, and even doing some breathing practices did not make me feel better. I felt I had lost something very important inside myself. A few days later the son of Adzom Drukpa came by on his way back from Central Tibet. I told him about this dream, and he said that, in fact, he had stopped to see her on his way and she had indicated by the way she spoke of time and so on that she would not live much longer. He thought probably my dream indicated that she would die soon.

So we did some Khadro Sangdu practice for three days to try to extend her life. In the Year of the Water Serpent, 1953, I was with my uncle on the mountain and taking NyingThig teachings when I received word she had left her body. I said a few prayers, as I did not know what else to do.

In the sixth month, I went to Dzongtsa, where she had died in her hut, and discovered that the servant Palden had died the same year. They said there were many auspicious signs at the time of his death. I met the Khenpo and the nun Zangmo who had served her, and Zangmo told me this story of her death: 'In the Year of the Water Serpent, Khadro said to us: 'Now I feel really old. I think in a little while I shall go!' She was 115 at the time.

We begged her not to go, but she said: 'Now bad times are coming and everything is going to change. There will be terrible problems and it's better I go now. In about three weeks I won't be here anymore. Start preparing for the funeral.

She instructed us precisely on how to conduct ourselves during the funeral and in preparation for it. She had an important statue of Padma Sambhava which she sent to Gyur Rinpoche, son of Adzom Drukpa. She left a little statue of Jamyang Khentse for Namkhai Norbu and various other things for Khenpo and her other disciples.

At the end, she opened herself completely to everyone who wanted to see her. During the last twenty days she stopped doing regular meditation periods and just saw people, giving advice and counsel to anyone who wanted it.

Near the twenty-fifth, without any sign of illness, we found that she had left her body at the time she would normally be finishing her meditation session. She remained in meditation posture for two weeks and when she had finished her tugdam, her body had become very small. We put some ornaments on it and many many people came to witness it.

In the second month on the tenth day, we cremated her. There were many interesting signs at the time of her death. There was a sudden thaw and everything burst into bloom. It was the middle of winter. There were many ringsel and, as she had instructed, all this and her clothes were put into the stupa that she had prepared at the Sakya monastery.

I, Namkhai Norbu, was given the little statue of Jamyang Khentse Wongpo and a volume of the Simhamukha Gongter and her writings and advice and spiritual songs. Among her disciples there were few rich and important people; her disciples were yogis and yoginis and practitioners from all over Tibet.

There are many tales told about her, but I have written only what she herself told me. This is just a little biography of A-Yu Khadro written for her disciples and those who are interested.

This text was written and verbally translated from Tibetan to Italian by Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche, and simultaneously orally translated into English by Barrie Simmons in Conway, Massachusetts, on the day of the dakini, 8 January 1983.

It was taped in Conway, then transcribed, edited, and annotated by Tsultrim Allione, finished in Rome, Italy on the day of the dakini, 7 February 1983.